Politics

History

U.S. History & Constitution

89 lessons

h total length

Create Your Account to Get Instant Access to “U.S. History & Constitution ”

Already have an account?

Lessons in this course

34:14

lesson 1

The Theory of the Declaration and the Constitution

The form of government prescribed by the Constitution is based on the timeless principles of the Declaration of Independence. These two documents establish the formal and final causes of the United States and make possible the freedom that is the birthright of all Americans.

43:28

lesson 2

Colonial Settlement

Nearly 170 years passed between the founding of the first colony in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 and the Declaration of Independence. Many of those who settled in the colonies during this period sought to escape persecution and to live a life according to their religious beliefs. A consideration of the writings of John Winthrop, William Penn, and William Byrd helps to illuminate early American colonial history.

26:29

lesson 3

Introduction

Good history presents an accurate picture of what happened in the past with a sympathy for those who lived before us. Studying the birth, growth, and survival of America—one of the most significant events in human history—provides foundational knowledge that we can apply to the challenges of our day.

30:14

lesson 4

Beginnings

America has stood as a land of hope from the time of the explorers. Yet Christopher Columbus—eager to find a trade route to the East—could not see the great import of his discovery.

11:51

lesson 5

The Declaration of Independence — Universals and Particulars

There is an indispensable relationship between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. This lesson explores the universal principles outlined in the Declaration and their implications for the form of just government. The argument of the Declaration culminates in the colonists’ solemn pledge to each other of their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor.

08:31

lesson 6

The Declaration of Independence — The Laws of Nature and of Nature's God

This lesson provides an account of the “general rule” or first authority cited in the Declaration of Independence—“the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” God is cited not only as a creator, but also as law-giver, protector, and judge—the implication being that only He can rightfully exercise all three functions of government. The meaning of the word “nature” is explained from its etymological roots to its revolutionary implications.

37:46

lesson 7

The Revolution of Self-Rule

The British imperial system fostered habits of self-rule in the American colonies, which were strengthened by the Great Awakening and the Enlightenment. This revolution of self-rule culminated in the resonant words of the Declaration of Independence, which cited “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.”

29:26

lesson 8

Natural Rights and the American Revolution

The principle of equality—which means no person may rule over another without his consent—is central to the political theory of the American Founding. Not only did it justify the Revolution, it also led to the creation of a government whose purpose is securing the natural rights of its citizens.

07:29

lesson 9

The Declaration of Independence — All Men Are Created Equal

This lesson draws upon the explanation of nature from the previous lesson to discuss one of its most important implications: equality. Far from an elaborate or vague concept, equality is a simple and clear principle, and is rooted in the fundamental human capacity to speak.

07:35

lesson 10

The Consent of the Governed

This lesson builds upon equality, the main idea in the previous lesson. It draws out the political implication from the principle that all men are created equal: no one among us can rule the rest unless we give that person permission to rule. Like the principle of equality, consent of the governed is of fundamental importance for understanding the government of the United States.

33:35

lesson 11

Enlightenment and Great Awakening

During the colonial period in both Britain and the American colonies, the existing religious establishment was undercut by a religious revival which embraced and preached the importance of religious enthusiasm. This Great Awakening, as it is called today, inspired self-confidence, less dependence on authority, and helped to prepare the way for the Enlightenment. The lives of George Whitefield and Benjamin Franklin exemplify the Great Awakening and the Enlightenment, and also the connection between these two important historical developments.

29:35

lesson 12

“To Secure These Rights”: Property, Morality, and Religion

While the first purpose of government is to protect citizens from foreign and domestic threats, it must also undertake other essential actions in order to secure natural rights. These include the protection of property rights, the defense of religious liberty, and the promotion of the moral character necessary to sustain free government.

37:00

lesson 13

Christianity and the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment’s elevation of reason and diminution of traditional authority posed challenges and presented opportunities to Christianity. The Christian response to the Enlightenment locates the mystery of humanity in the mysterious nature of the Creator of the universe in Whose image man is made.

34:25

lesson 14

The New Nation

After declaring independence from Great Britain, the Americans faced two monumental tasks. First, they had to defeat the mightiest military power in the world. Second, they had to establish a government capable of unifying the nation and securing their rights.

36:47

lesson 15

Majority Tyranny and the Necessity of the Union

The Articles of Confederation was America’s first attempt at establishing a national union. However, in many of the states, unchecked legislative majorities frequently trampled on the natural rights of minorities and disregarded the nearly powerless federal government. This experience of unstable and unjust government led to calls for a firmer union.

33:05

lesson 16

Introduction: Articles of Confederation and the Constitutional Convention

Written following the Constitutional Convention of 1787, The Federalist Papers is the foremost American contribution to political thought. Originally published as newspaper essays in New York, they were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pen name Publius. The essays defended the merits of the Constitution as a necessary and good replacement for the Articles of Confederation, which had proven defective as a means of governance.

36:48

lesson 17

The American Founding

In the 1760s, the British Parliament sought to exert its control over the quasi-independent American colonies by imposing taxes on them. However, the colonists, who had long since managed their own affairs, saw these actions as an attack on their natural rights and their rights as Englishmen. On July 4, 1776, the Americans declared their independence and founded a new nation.

30:55

lesson 18

The Improved Science of Politics

Publius argued that the “science of politics . . . has received great improvement” in his own day. These improvements include separation of powers, legislative checks and balances, judges who serve a life term during good behavior, and what he called “the ENLARGEMENT of the ORBIT” of government. Contrary to the practice of previous republics, Publius argued that a republic had a much greater chance of achieving success if it is spread out over a large or extended territory, rather than a small or contracted one.

27:30

lesson 19

Federalism and Republicanism

In the summer of 1787, the Framers labored to set up a political regime that would not only secure liberty and republicanism, but also bring energy and stability to the national government. Because of the failures of government under the Articles of Confederation, American political institutions were at risk. In order to secure these institutions, the Framers constructed a republican form of government that—among many other important features—instituted a new form of federalism.

20:03

lesson 20

The Experiment Begins, Part One

The brutal institution of slavery, which pre-dated the Founding of America, grew and became entrenched in the Southern states. Although it was antithetical to the principles of the Declaration of Independence, slavery survived the Constitutional Convention and became the great source of national dissolution.

10:30

lesson 21

Representation of the People

Representation is the means by which the principle of the consent of the governed is applied and maintained in the government. Without representation, the people lose their ability to consent. Therefore a mechanism is necessary by means of which the people can regularly express their consent. For the United States, this mechanism is the Constitution. Ultimately, representation allows for citizens to entrust the governing of the country to a few people while still retaining the crucial ability to control the power of the government. This feature provides a beneficial check both on the people and on the government, and thus is favorable to liberty.

27:46

lesson 22

Separation of Powers

In constituting a new government, the Framers knew that written rules—what Publius calls “parchment barriers”—would not be enough by themselves to protect liberty and prevent tyranny. Instead, Publius looks to the “interior structure” as the best means for keeping the branches properly and effectively separated. Separation of powers, the most important of the Constitution’s “auxiliary precautions,” works to prevent governmental tyranny, and by keeping each branch within its proper sphere of authority allows each branch to do its job well.

11:01

lesson 23

The Separation of Powers

Built on the principles of equality, consent, and rule of the majority, the Constitution provides the sovereign people with the means for effective and reasonable self-governance. As the sovereign, the people separate the three functions of government into departments and delegate specific powers to each, which protects against tyranny and preserves liberty. To that end, the principle of separation of powers helps the people maintain control of their government.

11:09

lesson 24

Sovereignty and Power

This lesson explores the question of sovereignty in the United States. In a representative and federal government, it is sometimes difficult to see who has the supreme authority, or the final say in matters of great importance. The principles of American government, however, require the sovereignty of the people. They express their will through a constitutional majority, although they themselves do not rule directly.

29:40

lesson 25

The Legislative: House and Senate

The Founders understood that the legislative branch is by nature the most powerful in a republican government. Experience of government under the Articles of Confederation, when state legislatures routinely encroached on executive and judicial powers, confirmed this. Thus, the Framers divided the legislative branch into two parts—the House and the Senate. In addition, they differentiated them as much as possible, consistent with the principles of republican government, with the goal of preventing tyranny and encouraging good government.

26:58

lesson 26

The Legislative Power

To exercise legislative power properly, legislators must deliberate. The Framers of the Constitution designed Congress to engage in reasoned deliberation and produce good laws, equally applicable to all. This capacity has been lost due to modern developments in the American regime.

35:14

lesson 27

The Executive

Following their experience under the Articles of Confederation, and armed with the improved science of politics, the Framers instituted a unitary executive in the office of the president. Unlike the executive office in any previous republic, it was designed so as to ensure energy and responsibility in the executive, which are absolutely essential for good execution of the laws, and therefore for good government.

41:32

lesson 28

The Executive Power and the Constitution, Part 1

The institution of the presidency as established by the American Founders has been drastically altered over the course of the last century. The modern executive branch spends most of its time and energy engaged in unconstitutional activities, while neglecting many of its constitutional obligations. Whereas the American Founders thought the purpose of government should be the protection of every citizen’s natural rights, today’s government— by means of a bureaucracy nominally overseen by the president—is oriented toward the protection of certain classes of citizens and detailed management of society’s problems. By contrast, the Founders thought that rights should be protected by all three branches: they are defined in law by Congress, violations thereof are adjudicated in the courts, and those who violate the rights of others are punished, according to law, by the executive.

38:20

lesson 29

The Executive Power and the Constitution, Part 2

In the Constitution, the president is given three domestic powers: the power to execute the laws; the power to appoint executive branch officers with the advice and consent of the Senate; and the power to require written opinions from the heads of executive departments. The chief executive also has a role in the legislative process: the president holds the veto power, the power to make recommendations to Congress, the power to convene Congress, and, in the case of disagreement between the two houses of Congress, to adjourn it. The modern presidency has failed at one of its fundamental tasks—enforcing the laws passed by Congress—thereby threatening the rights of American citizens.

29:38

lesson 30

The Judiciary

In the Declaration of Independence, one charge leveled against King George III was that he had “made Judges dependent on his Will alone.” In framing a republican government, the Founders believed that an independent judiciary was indispensable. Publius argues that the term of life tenure during good behavior and a protected salary ensure this independence.

25:54

lesson 31

“The Constitution Is Itself . . . a Bill of Rights”

In Federalist 84, Publius writes, “The truth is, after all the declamation we have heard, that the constitution is itself, in every rational sense, and to every useful purpose, A BILL OF RIGHTS.” In other words, the structure of the Constitution protects the rights of the people. In addition, the American people retain all powers not granted to the federal and state governments.

08:52

lesson 32

Reason and Passion

This lesson explores an important problem latent in majority rule. If the majority has the right to express the will of the people as a whole, it is important that its decisions be products of calm reason and not volatile passions. A democracy is just as capable as a monarchy of becoming tyrannical. Therefore the Founders designed the Constitution to enable the people as much as possible to make well-reasoned laws that are beneficial to the common good.

22:15

lesson 33

The Experiment Begins, Part Two

The American experiment in self-government was contentious from the beginning, as leading citizens were divided over the policies needed to protect rights and promote happiness. During this period, George Washington proved indispensable as the new nation’s first president.

09:20

lesson 34

The Necessity of Virtue

While the separation of powers is the greatest of the institutional restraints on government, the principal restraint is a virtuous people. Ultimately, the maintenance of free government depends on the people themselves. Auxiliary precautions such as separation of powers and checks and balances are necessary, but they are insufficient. Experience has shown that a people will either be virtuous and free or else corrupt and ruled.

32:09

lesson 35

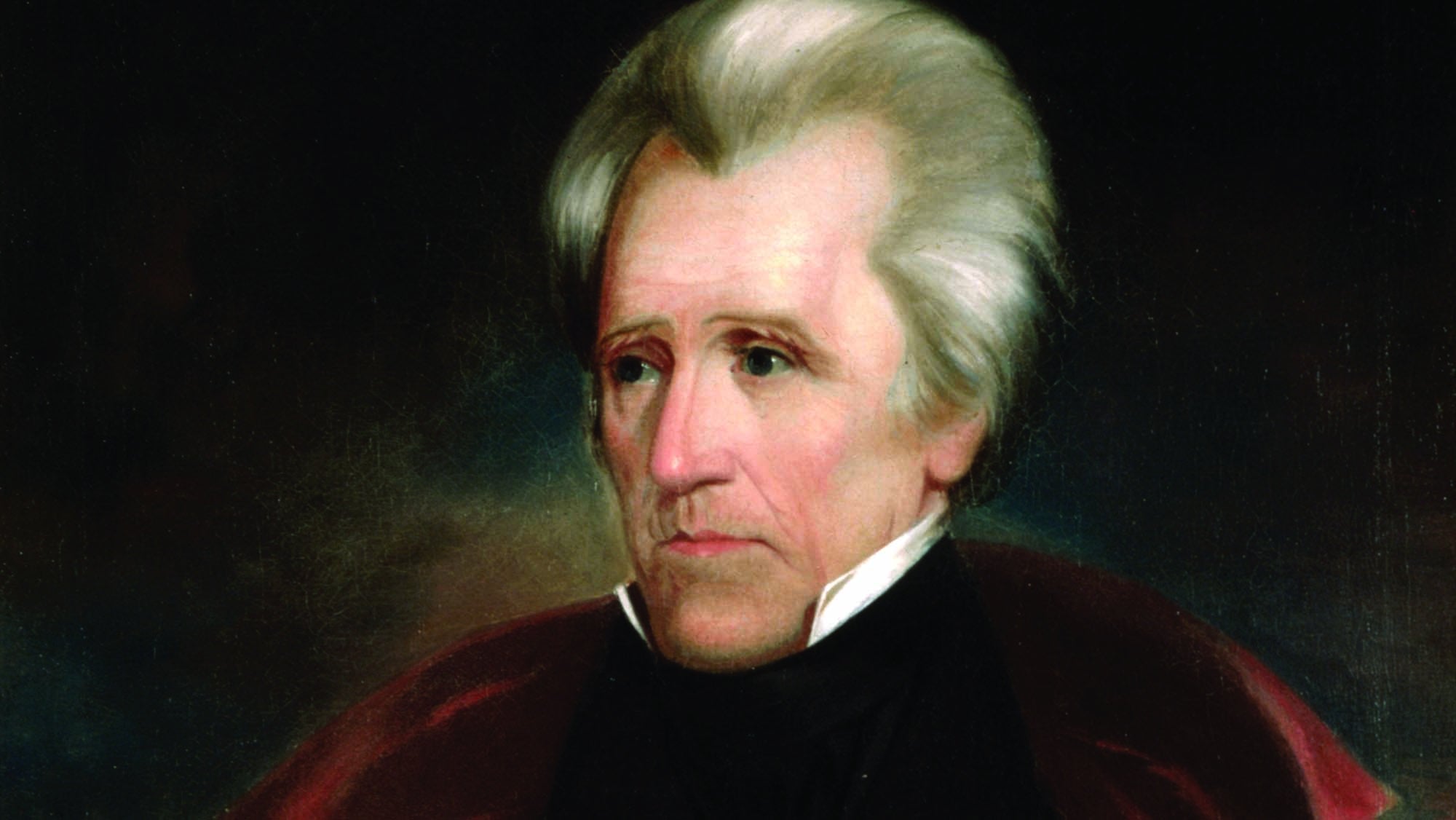

Jacksonian Democracy

The era of Jacksonian Democracy—which stretched from the early 1800s to just before the Civil War—was characterized by several prominent national issues that were the subject of great controversy, including the rise of evangelical religion and the problem of slavery. This period also saw the rise of individualism and great advances in technology, as the nation expanded ever further westward.

28:55

lesson 36

The Culture of Democracy and Its Shadow, Part One

The election of Andrew Jackson in 1828 marked the beginning of a more democratic age, which brought important changes to many areas of American life, including politics, religion, and the arts.

17:12

lesson 37

The Culture of Democracy and Its Shadow, Part Two

As the North entered its age of democracy, the institution of slavery dominated the politics and economics of the antebellum South.

33:43

lesson 38

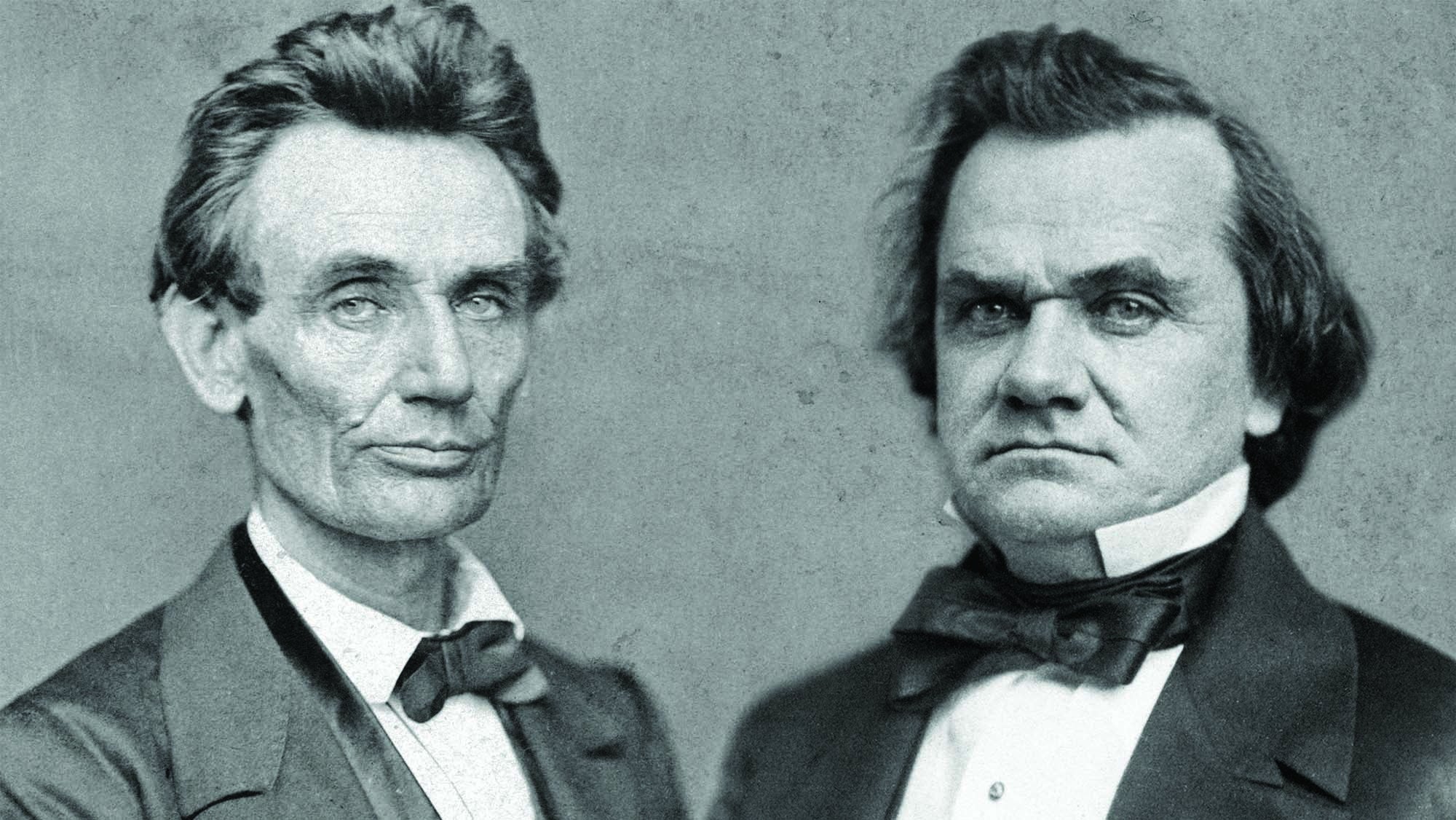

The Crisis of the Union

The crisis of the Union that culminated in the Civil War had its roots in a fundamental disagreement over the meaning of the Declaration of Independence. Some prominent politicians, including Stephen Douglas, argued that the Declaration’s principles applied only to white men, and the solution to the slavery problem was popular sovereignty. Abraham Lincoln, by contrast, believed as the founders did that those principles are universal and timeless, and that they pointed toward slavery’s eventual abolition.

32:26

lesson 39

The House Divides, Part One

The Mexican War of 1846 pushed the United States toward a civil war by reviving the national debate concerning slavery in U.S. territories—a debate that the Missouri Compromise had attempted to settle in 1820.

33:01

lesson 40

Western Expansion

The Northwest Ordinance is an essential part of western expansion in the United States. One of the four organic laws of the United States, the Ordinance, which was passed in 1787, protected civil and religious liberty and prohibited slavery. This early expansion, made possible by the Ordinance, and subsequent explorations of the West, including most notably the Lewis and Clark expedition, laid the groundwork for American expansion further westward.

16:20

lesson 41

The House Divides, Part Two

In the wake of Southern rebellion, Abraham Lincoln faced the complicated task of winning a war and restoring the bonds of affection necessary for Union.

29:00

lesson 42

Reconstruction and Transformation, Part One

As the Civil War ended, America entered a period of reconstruction in an attempt to recover from the war’s devastation and find just terms for a settlement between the sections.

09:56

lesson 43

Ballots Rather Than Bullets

The Declaration of Independence asserts that government is legitimate only when the people consent to it. The election of 1800 demonstrated the legitimacy of the American system of government because the people were able to assert their will and change the government, according to the strictures of the Constitution. With the election of Thomas Jefferson to the presidency, the American people effected a change of government without firing a shot.

23:30

lesson 44

The Progressive Era, Part One

The progressives attempted to address the challenges posed by modern American life through a series of institutional changes that conflicted with the founders’ understanding of constitutional government.

24:45

lesson 45

The Progressive Era, Part Two

Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson championed progressive philosophy in their efforts to transform the presidency and other American institutions.

39:22

lesson 46

Woodrow Wilson and the Rejection of the Founders’ Principles

Progressives believe that America needs to move beyond the principles of the Founding. Woodrow Wilson—who served as president of Princeton University, governor of New Jersey, and as America’s 28th president—was one of the earliest Progressive thinkers. His critique of the Founding—namely, his rejection of the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution’s system of the separation of powers—is one of the most articulate expressions of the Progressive movement’s core beliefs.

31:49

lesson 47

Progressive Era Congressional Reform

As Progressives grew disenchanted with a powerful Speaker of the House, they began a process of decentralizing power in both legislative chambers. This process persisted throughout most of the twentieth century.

33:08

lesson 48

Progressivism

Near the end of the nineteenth century, Progressive political theorists began to view the principles of the American founding as archaic and obstructive. They argued that the modern age brought with it new problems, which required new principles, as well as a move away from the republicanism of the founding to a state ruled by administrative experts. Progressivism came to dominate American politics in the 20th century, and remains a powerful political force today.

36:30

lesson 49

The Progressives and Presidential Leadership

Many features of today’s presidency originated in the Progressive Era. Progressive leaders, including Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, sharply criticized American political institutions and the Founding principles on which they were built. In particular, Progressives believed that the separation of powers and other constitutional limits on federal power were antiquated, prohibitive, and unnecessary. To break these constitutional shackles, Progressives turned to the office of the presidency, which they thought could transcend such limits by becoming a steward of the people’s will.

22:41

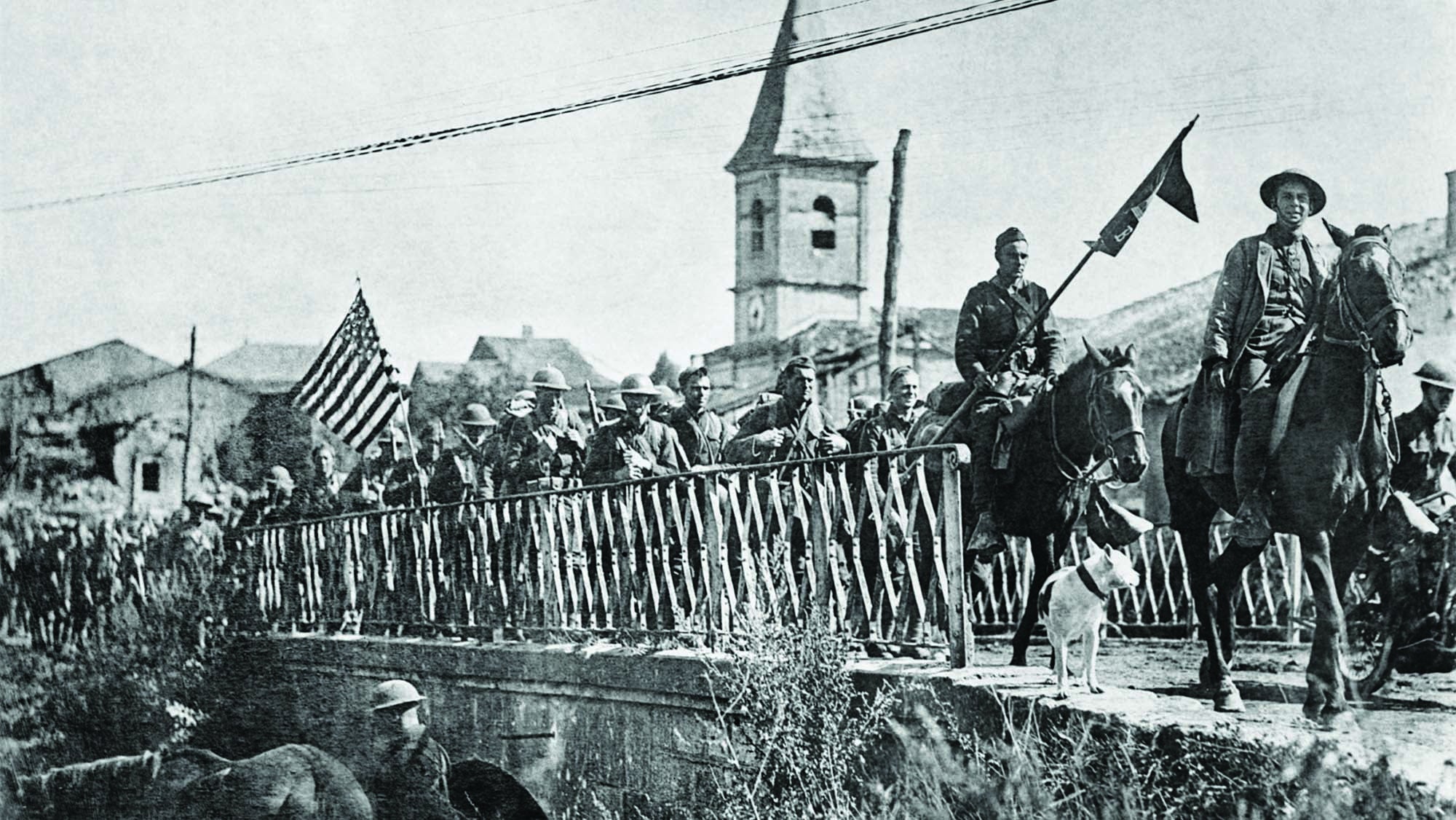

lesson 50

The Great War and Its Aftermath, Part One

Despite efforts to remain neutral, the United States entered World War I in 1917. The Americans helped the Allied powers secure victory a year later. The war took the lives of millions, and resulted in immense destruction and political instability in Europe and beyond.

25:58

lesson 51

The Great War and Its Aftermath, Part Two

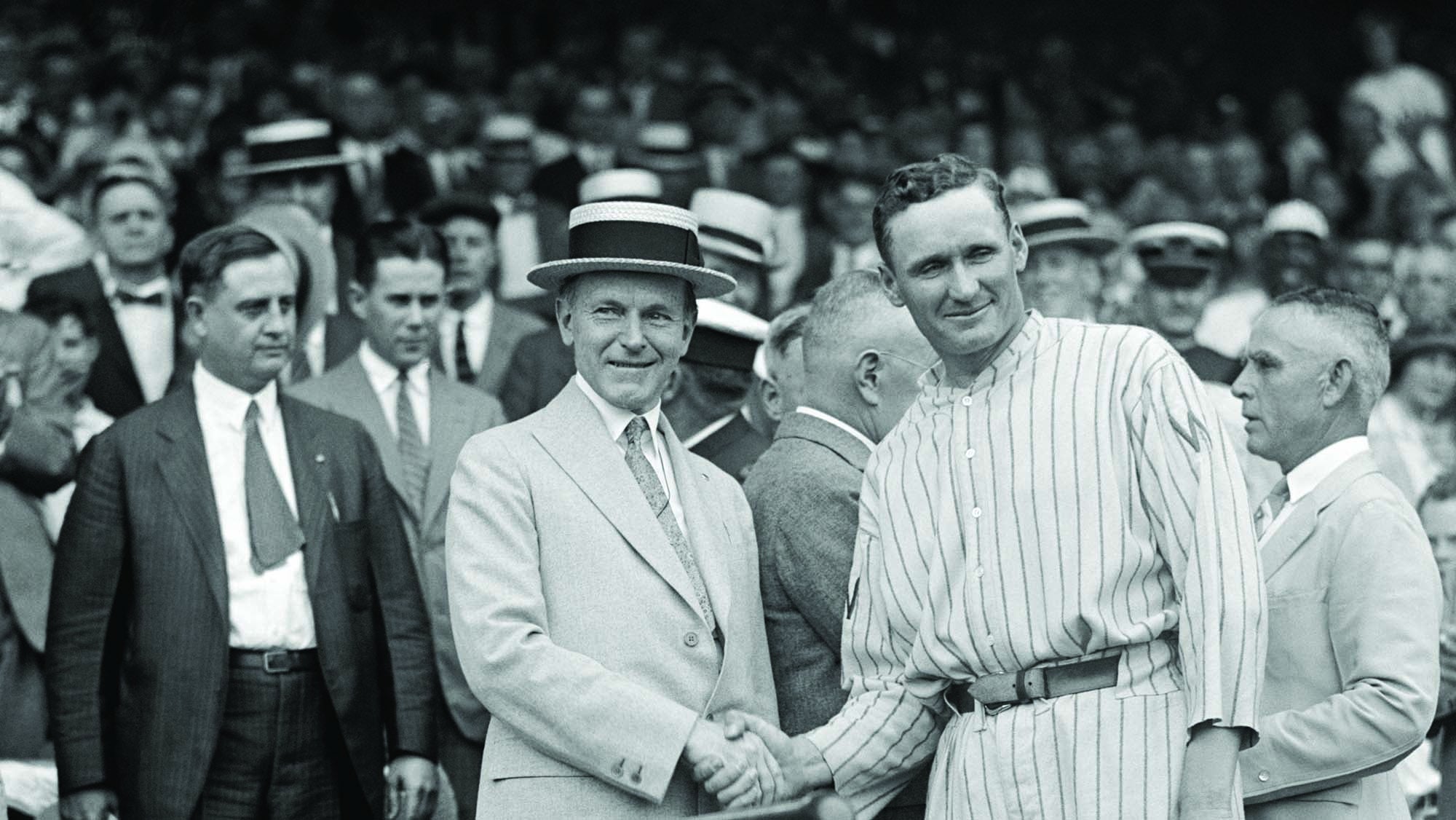

Following Woodrow Wilson’s failure to achieve his ambitious international goals, the presidents of the 1920s focused on American prosperity and enterprise.

27:11

lesson 52

Lochner v. New York: Property Rights

The American founders held the view that the right to property is a natural right possessed by all human beings and that the fundamental purpose of the Constitution is to secure the natural rights of all American citizens. For many decades after the founding, the U.S. Supreme Court remained faithful to this purpose. Beginning in the late 19th century, the Supreme Court embraced the doctrine of substantive due process, which gradually undermined the founders’ understanding of property rights.

35:52

lesson 53

Woodrow Wilson and the Rejection of the Founders’ Constitution

Woodrow Wilson argued that the separation of powers established by the Constitution prevented truly democratic government. In order to render government more accountable to public opinion, Wilson held that the business of politics—namely, elections—should be separated from the administration of government, which would be overseen by nonpartisan, and therefore neutral, experts. The president, as the only nationally elected public official, best embodies the will of the people, resulting in a legislative mandate.

31:02

lesson 54

The New Deal

In the midst of the Great Depression, Americans turned to Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his New Deal. The bevy of programs and new government agencies created under FDR did not solve the problems resulting from economic depression.

42:42

lesson 55

Overview: Founders vs. Progressives

Progressivism represents a radical departure from the Founders’ understanding of the purpose and ends of government. Comparing and contrasting the arguments of the Founders and of the Progressives regarding six key principles of government—the meaning of freedom; the purpose of government arising from the meaning of freedom; the elements of domestic policy; the extent of foreign policy; the centrality of the consent of the governed; and the size and scope of government—shows decisively that Progressivism is not a logical outcome of the Founders’ principles, but rather a conscious rejection of them.

36:20

lesson 56

The Stakes of World War II

World War II can be understood in terms of two competing arguments regarding the nature of man. One argument views man primarily as part of a collective, shaped in decisive respects by race or class. This led to the invasion of peaceful lands and the organized slaughter of millions. The other argument views the human soul as free—never to be governed without consent. The unflinching insistence on this view led to liberation.

34:52

lesson 57

FDR’s New Bill of Rights

Thoroughly educated in Progressive principles, Franklin D. Roosevelt believed that the task of statesmanship is to redefine our rights “in the terms of a changing and growing social order.” While the Founders thought the truths they celebrated in the Declaration of Independence were self-evident and so also timeless and unchanging, FDR argued for a new self-evident economic truth. His proposed “Economic Bill of Rights” lays out the means by which our new economic rights are to be secured, thereby achieving social equality and social justice.

39:48

lesson 58

The Finest Hour

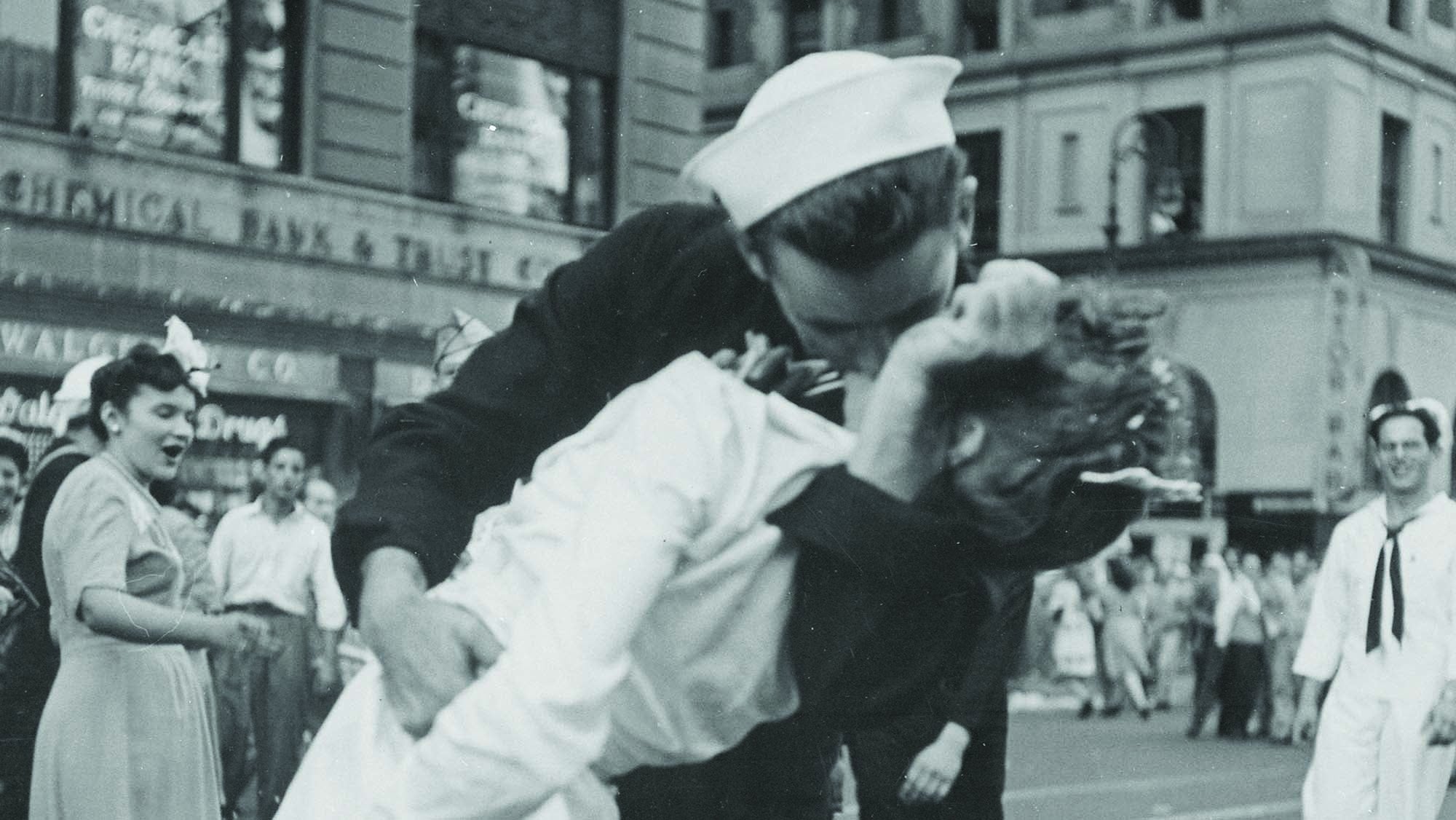

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor spurred Americans to enter World War II. The economic and industrial might of the United States helped secure a decisive Allied victory, and the United States emerged from the war as a world superpower.

27:50

lesson 59

A Time of Turbulence, Part One

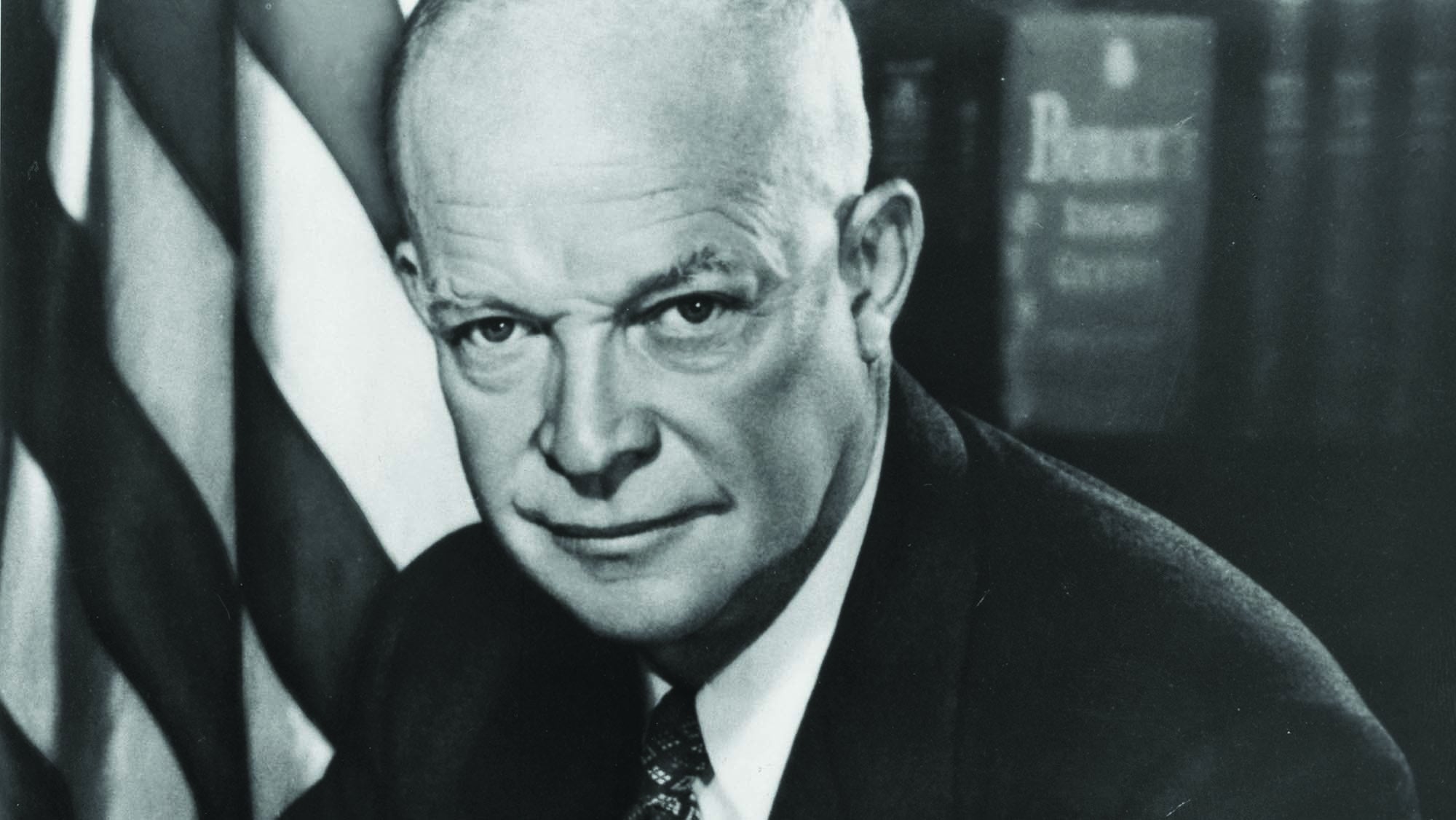

Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower pursued a post-war foreign policy of containing the growing threat of the Soviet Union and the spread of communism.

17:10

lesson 60

A Time of Turbulence, Part Two

John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke of America as a land of hope, as the former dealt with the Soviet Union abroad and the latter confronted racial inequality at home.

38:49

lesson 61

America as World Power

Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson warned against permanent entangling alliances. Yet, as the United States grew economically, and as challenges to domestic security arose from abroad, America’s role on the world stage changed dramatically. Over the course of the 20th century, America grew to become the preeminent global power.

32:36

lesson 62

Brown v. Board of Education: Civil Rights

The Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. The decision contributed to the establishment in the 20th century of the Supreme Court as the final arbiter of the Constitution. This outcome is contrary to the founders’ understanding of three co-equal branches, all of which have a duty to interpret the Constitution.

20:55

lesson 63

Rise and Fall, Part One

Lyndon B. Johnson entered office with an ambitious plan to expand the scope of government. Dubbed “The Great Society,” his efforts to transform domestic policy were stalled in part by his party’s opposition to America’s mounting commitments in Southeast Asia.

37:35

lesson 64

Post-1965 Progressivism

Post-1965 Progressivism is an incoherent blend of the earlier Progressive emphasis on material and spiritual uplift coupled with a new, adamantly relativistic orientation. This altered Progressivism champions an understanding of freedom as “the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the meaning of human life.” Policies that attack the traditional family through the promotion of sexual liberation, the redefinition of racial equality in terms of atonement for alleged historical victimization, and a preference for the preservation of the environment over human flourishing—demonstrate that post-1965 Progressivism not only rejects the ethical ideal of earlier Progressivism; it also denies the Founders’ conception of equality and rights as grounded in “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.”

37:05

lesson 65

Congressional Reform in the 1970s - Part 1

In the 1970s, Congress acted on a variety of fronts to strengthen itself and to restrain the presidency and regulatory bureaucracies. These actions helped to undermine belief in the capacity of the president to govern effectively.

40:39

lesson 66

Post-1960s America

In the twentieth century, technological advances brought material prosperity, but also made the threat of large-scale modern war ever-present. To counter this threat, government must craft proper policy towards other nations and employ deterrents to war. With the rise of the administrative state and of the belief in scientific progress, politicians began declaring war on conditions of human life that the American founders thought were permanent. Both kinds of war pose a threat to liberty, as they require tremendous resources and impose great burdens on the citizenry.

34:14

lesson 67

Roe v. Wade: Privacy and Liberty

The Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade declared a right to an abortion as part of a right to privacy—a term not found in the Constitution. The Court’s second landmark decision on the issue, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, gave abortion rights a new grounding in an understanding of liberty that marked an explicit rejection of the founders’ belief in an unchanging human nature. Both cases touch on fundamental questions of morality, liberty, and government power.

28:01

lesson 68

Rise and Fall, Part Two

While Richard Nixon achieved important diplomatic victories in Vietnam and China, the American economy suffered from low growth and inflation. Nixon’s resignation, and the failures of the Carter administration, diminished America’s confidence in the presidency.

34:11

lesson 69

The Beloved Community or Black Separatism?: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 represent two of the most important achievements of the civil rights movement in America. Despite these achievements, Americans were split regarding the best tactics for ensuring the protection of civil and political rights for black Americans. While Martin Luther King, Jr. preached non-violent direct action and racial reconciliation, Malcolm X rejected American politics and advocated black separatism.

37:45

lesson 70

Rhetoric and the Modern Presidency

The use of rhetoric by Progressive presidents, beginning in the early 20th century, has transformed the way that Americans think about the presidency. No longer is the president viewed as the head of one institution in a tripartite system of separated government powers that is designed to secure the natural rights of all American citizens. Rather, the president is today considered a national political leader who is expected to wield the powers of government in order to satisfy the needs of the people. To execute this political role, the modern president primarily relies on three rhetorical techniques: he employs a wartime mentality, provides a vision for the future, and offers himself as an indispensable leader who can address the problems of the day.

35:33

lesson 71

Congressional Reform in the 1970s - Part 2

In the 1970s, Congress acted on a variety of fronts to strengthen itself and to restrain the presidency and regulatory bureaucracies. These actions helped to undermine belief in the capacity of the president to govern effectively.

19:58

lesson 72

The Path of Renewal, Part One

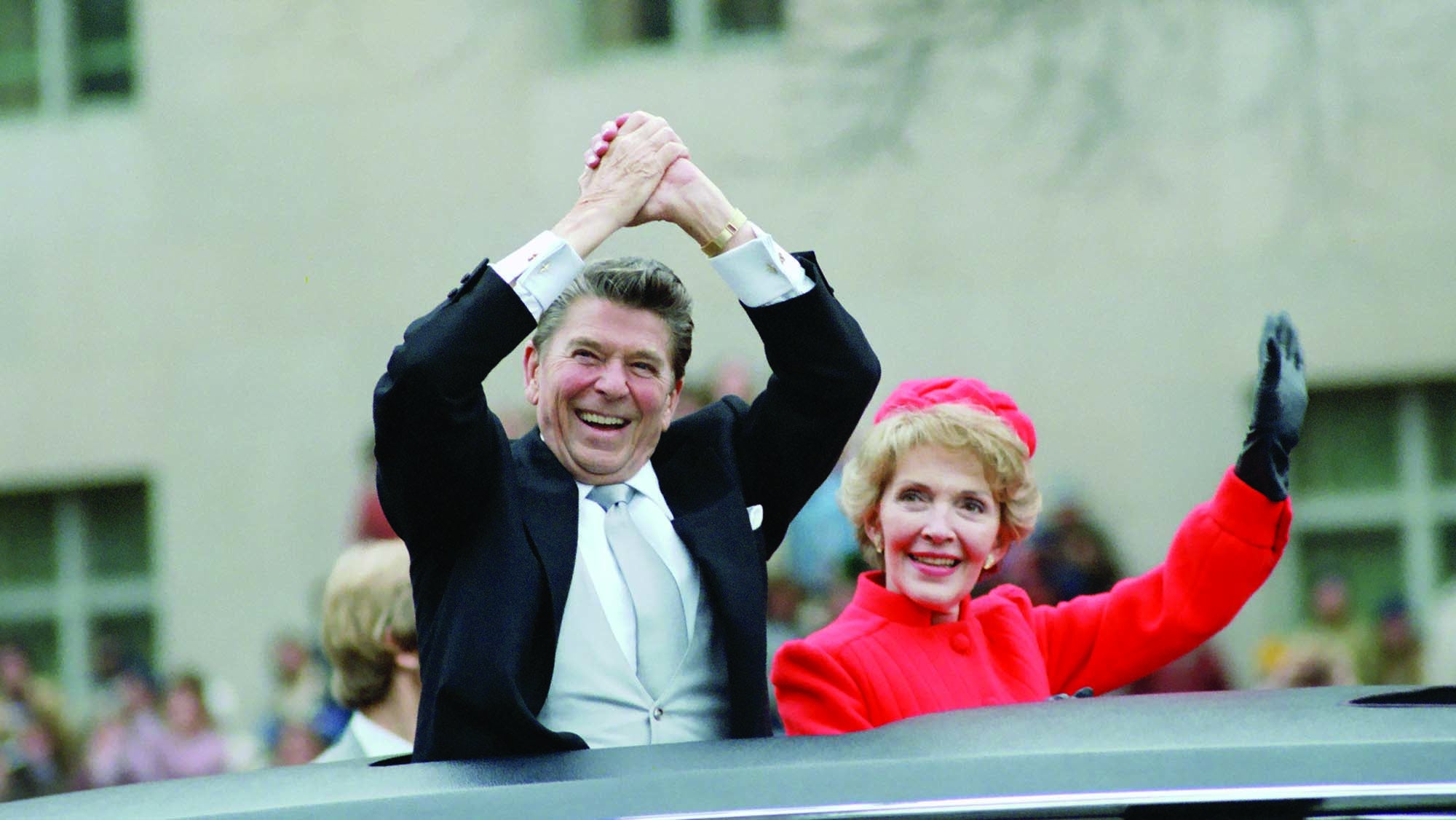

Ronald Reagan restored the office of the presidency to its place of prominence through policies that fostered a productive economy and that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union and an end to the Cold War.

31:06

lesson 73

The Imperial Presidency

A troubling feature of the modern presidency, which has expanded rapidly under the Obama Administration, is a brazen disregard for constitutional limits and the law. Contrary to the framework of the Constitution, which depends on competition among the three branches of government, Congress and the courts have been increasingly complacent in the face of, and often compliant with, the development of this feature. Over the course of the last century, particularly since the 1960s, these institutions have enabled the modern executive branch to exercise all three powers of government in the regulation of nearly all aspects of everyday life.

30:58

lesson 74

The Modern Congress - Part 1

The founders sought to create a system of government in which reason and deliberation would rule, rather than passion. The theory of legislative power they developed to achieve this good was based on two essential elements: the extended republic and the separation of powers. Progressive reformers rejected both the Founders’ conception of the problem as well as their solution.

29:45

lesson 75

The Path of Renewal, Part Two

Despite the optimism that surrounded the end of the Cold War, the decades since have seen the United States divided over a series of important issues. To restore our common purpose, Americans should learn from the great examples of our nation’s past.

32:17

lesson 76

The Modern Congress - Part 2

The founders sought to create a system of government in which reason and deliberation would rule, rather than passion. The theory of legislative power they developed to achieve this good was based on two essential elements: the extended republic and the separation of powers. Progressive reformers rejected both the founders’ conception of the problem as well as their solution.

34:17

lesson 77

D.C. v. Heller: Second Amendment

The Second Amendment to the Constitution states, “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” The Supreme Court has examined a number of cases involving the right to keep and bear arms. But D.C. v. Heller was the first Court decision to scrutinize carefully the text of the Second Amendment, as well as its history and purpose.

27:55

lesson 78

Identity Politics Today

Identity politics holds that America is fundamentally and irredeemably racist. This ideology, which has become dominant in American public life, requires discrimination in order to elevate and privilege the identities of the oppressed.

37:05

lesson 79

The War Power

The president serves as commander in chief of the armed forces, and he also has the power and responsibility to direct the foreign affairs of the nation. However, the Framers of the Constitution were careful to limit the president’s war power by vesting the powers to declare and fund war in Congress. The Founders believed that the fundamental object of any foreign policy should be America’s safety and independence, for the sake of protecting American citizens’ rights. The Progressive view of foreign policy and the war power—which marks a rejection of this principled position—has transformed America into an exporter of ever-changing political ideals.

35:53

lesson 80

The Administrative Presidency

A central tenet of Progressivism is the rejection of the president’s constitutional role as chief executive. In response, presidents from both parties have sought other forms of governance. These forms, which have become mainstays of the modern presidency, center power in the White House and depend on regulatory review and a large administrative apparatus. Far from the Lincoln White House, in which the president had two assistants, today’s White House is full of administrators who help to oversee an ever-expanding bureaucratic state.

42:57

lesson 81

Chevron v. NRDC: Administrative Law

In Chevron v. NRDC, the Supreme Court adopted what is known today as the Chevron Doctrine. This means the Court defers to an agency’s policy decisions, as well as to that agency’s determinations concerning the scope of its own power. Judicial deference to the administrative state—enabled by the congressional delegation of power—poses a serious threat to limited, constitutional government.

22:58

lesson 82

Conclusion

After undergoing a transformation that began in the Progressive Era, Congress today stands in opposition to the founders’ Constitution. As Congress continues to delegate its legislative authority to bureaucratic agencies, it loses ever more control over decisions reserved to it by the Constitution. The solution is a return to constitutional government, which requires a change in public opinion.

14:29

lesson 83

The Problem with Progressivism

Progressivism asserts a new view of the purpose of American government. This political philosophy seeks to replace Founding principles—such as equality, consent of the governed, and separation of powers—with the belief that all ideas are true only in the contexts in which they develop. As a result, Progressives believe the universal and timeless claims of the Declaration of Independence, which serve as the foundation of American constitutionalism, are no longer true or relevant today.

31:53

lesson 84

Conclusion: Constitutionalism Today

American government today is much different from the constitutional republic outlined in The Federalist Papers—which relies on structure, representation, and limitations on the functions of the federal government. Administrative regulations and entitlements are two distinguishing features of modern government. These new features require a kind of government that is unlimited, disregards separation of powers, and violates the supreme law under which it claims to operate.

37:30

lesson 85

The Supreme Court Today

Today’s Supreme Court holds great power to shape American society, contrary to the Founders’ view of the Court as the “least dangerous” branch. To put this power in the hands of judges who believe the Constitution does not have a fixed meaning poses a serious threat to freedom. Returning the Court to its proper role as a bulwark of limited, constitutional government is essential for the preservation of liberty.

36:41

lesson 86

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby: Religious Liberty

The First Amendment to the Constitution states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Over the course of American history, but beginning especially in the 20th century, the Supreme Court has heard numerous cases related to the right to religious liberty. While the fundamental issue has always been the proper relationship between individual liberty and the political community, many contemporary legal disputes about religious liberty have arisen as a result of a changing popular culture.

40:33

lesson 87

Case Study: Religious Liberty in the Administrative State

Post-1960s Progressivism has steadily eroded religious liberty and the freedom of association in America. Measures such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and many anti-discrimination laws express a new understanding of rights that rejects the Founders’ view of religious liberty and the freedom of private associations to govern themselves. Recent Progressivism follows the early Progressive belief that effective freedom requires government to redistribute resources in order to provide equal access to the goods that promote mental development and that make life comfortable. This redistributive agenda is combined with a new emphasis on the empowerment of victim groups, sexual liberation, and an aversion to traditional Christianity and Judaism that requires government intervention in the internal affairs of private organizations. Religious liberty today is divorced from the freedom of association and the free exercise of religion, which the Founders understood to be essential for a free society.

38:41

lesson 88

Restoring Constitutional Government

The past century has witnessed a transformation in the understanding of the purposes of American government. The political, academic, and media consensus today upholds the necessity and legitimacy of the Progressive project, making a return to the principles of the Founders appear difficult, if not impossible. However, the resonance among voters of appeals made to the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution by Calvin Coolidge and Ronald Reagan highlights the enduring character of those self-evident truths upon which the Founders built the American political order.

30:55

lesson 89

Conclusion: Reviving the Constitutional Executive Power

The Founders placed the executive power in the hands of a unitary officeholder, the President of the United States. This unity enables the president to act decisively and ensures that he will be held accountable for his actions. The office was designed to be limited and to be checked by two other branches. By contrast, modern government is run chiefly by unaccountable executive-branch bureaucrats who hold all three powers—legislative, executive, and judicial—of government. In order to avert the crisis presented by this unconstitutional combination of powers, citizens must work to understand the principles of the Founders’ Constitution, and seek to apply these principles to contemporary politics.

What Current Students Are Saying

Takes the student through the full context of the course subject matter. Wonderful insight into how we strayed and its consequences and offers a solution.

Create your FREE account today!

All you need to access our courses and start learning today is your email address.